On November 19, 1998, a young, unproven studio released their debut title after a one-year delay that led to the game’s first iteration being scrapped entirely in order to start fresh. Against all odds, this title would completely revolutionize the videogame industry and set a new standard for storytelling in games and for the then nascent first-person shooter genre.

Almost twenty-five years later, Valve Software’s Half-Life is still widely considered one of the greatest games ever made. However, as older titles like Doom and Quake regain their popularity and influence a revival of the so-called “boomer shooter” subgenre, does Half-Life still stand the test of time? And for newer players, is there still a point to play the original when there’s a full-blown remake in a newer engine released just a few years ago?

That’s what we’re here to find out. Let’s take a trip back to the Black Mesa Research Facility and reevaluate the game that started it all.

Ludonarrative resonance

Back in the day, Half-Life was a game-changer due in large part to its incredibly immersive storytelling. Whereas its contemporary shooters tended to drop the player into a maze-like first level with a starting gun and let them cut loose, Half-Life takes its time to show off the bowels of the research facility where the game takes place, then drops the player into the daily life of a scientist running late for a big experiment.

For its day, it was completely new and unexpected and did wonders for the sense of place, setting up Black Mesa before it all quickly goes to hell and forces you to run, think and shoot to survive. For the modern age, it may look quaint and even slow, with modern titles once again taking a lot less time to drop players into the action—but, arguably, this only helps Half-Life’s approach stand out again, decades after it set the trend in the first place.

Sure, it’s impossible to deny that the Goldsource engine is showing its age—even if you apply the infamous High-Definition Pack models created by Gearbox for its expansion, Half-Life: Blue Shift, at the extra cost of a lot of the game’s charm—and nowadays, indistinguishable NPCs with barely five lines of repeating dialogue are hardly impressive, but these early chapters still do wonders to set up Half-Life’s most impressive and lasting trick: atmosphere.

By virtue of its world-building, the lack of cutscenes interrupting gameplay (something that should have become more of a trend, but never did) and the fantastic artistry of its time dripping from every model and texture, Half-Life oozes atmosphere at every turn, never more so than right after the resonance cascade brings xenotheric creatures into the previously peaceful halls of Black Mesa.

Run, think, shoot, live

It doesn’t take too long for things to go horribly wrong and for you, as 27-year-old research associate Gordon Freeman, to find yourself armed with a crowbar and, soon after, a handgun, which will see plenty of use dispatching your former colleagues, now mutated by parasitic headcrabs into zombies, and other alien monstrosities such as ceiling-dwelling barnacles and packs of ear-bursting houndeyes as you try to find a way out of the facility.

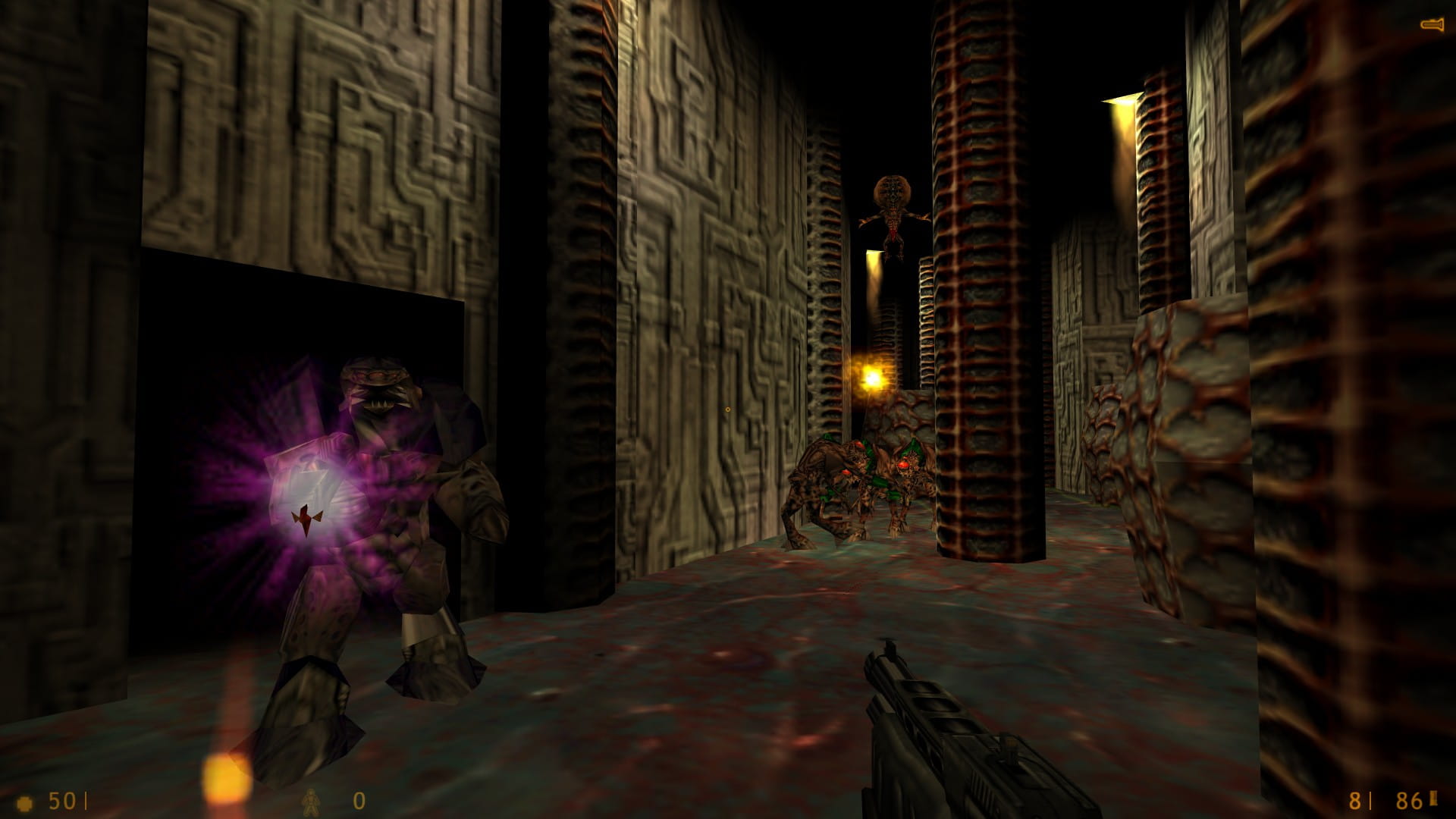

Half-Life’s quality is consistent enough—barring one notable exception we’ll get to—that plenty of debates have been had in regards to what part of the game is its best, but I’m of the opinion that the first few chapters are the game at its absolute peak, thanks in no small part to the aforementioned atmosphere. Office Complex in particular is a strong sample of the variety of gameplay in the game, mixing puzzles, jumping sections, (too many) vents, sentry guns you have to evade and close quarters combat against vortigaunts.

With that said, there’s something in Half-Life for everyone. Don’t love crawling through the scary and atmospheric remains of the facility with nothing but a crowbar and a pistol? Not to worry, you’ll soon be up on the surface, armed to the teeth and fighting a horde of Marines hell-bent on “cleaning up” the facility by killing any surviving witnesses. If that’s not your style, then perhaps you’ll prefer the jumping sections in Residue Processing, or riding a cart in On A Rail (although nobody seems to like that very much), or perhaps even blowing up helicopters on the cliffsides of New Mexico in Surface Tension. Is Jaws your favorite movie? You’ll love Apprehension and the teethy new friends you’ll make in its waters. Like tentacles? You’ll have a blast in Blast Pit!

A lot of newer players nowadays tend to frown upon Half-Life as somehow unoriginal, ironically desensitized to many of the tropes it pioneered in the first place. But there can be little debate that there’s no variety in its 7-to-10-hours playtime; the game always has something new to throw at you, some weapon or enemy or situation that you haven’t encountered before, and the description above is hardly a complete picture of everything you go through as Gordon Freeman as you try to escape the chaos you yourself caused.

That’ll look nice in my trophy room

The gunplay itself has also been hotly debated in the past quarter of a century, with opinions varying from “terrible” to “okay”. Compared to modern titles, it’s certainly more primitive, but seeing as the genre’s early years have had a resurgence of late, there’s clearly something timeless about the gameplay of ’90s FPS games. While preferences are a matter of opinion, I’d argue the mechanics of Half-Life’s shooting have aged gracefully—it’s certainly “run and shoot” and usually not incredibly accurate, but in the midst of being overwhelmed by zombies or in a firefight with grunts, it’s still very enjoyable, some would argue even more so than its sequel.

There’s a healthy variety of weapons too, and while there’s nothing as egregious as, say, Duke Nukem 3D’s Shrinker, you get plenty of fun toys, like the fan-favorite Tau cannon, the “Ghostbusters called, they want their proton packs back” Gluon gun and the delightfully chaotic Snarks that are both weapon and foe, although the more mundane equipment can be a bit underwhelming; the pistol is basically a peashooter, the SMG isn’t very impactful and the shotgun lacks a bit of heft, though the crossbow, as opposed to a more traditional sniper rifle, is a highly entertaining and effective alternative and the .357 revolver satisfyingly brings the thunder.

The arsenal would be meaningless if there aren’t interesting foes to use it against, but thankfully, Half-Life has those in spades. The headcrabs are little more than a horrifying nuisance and the zombies can be dispatched with just the crowbar with some practice, but the “alien slaves”, a.k.a. the vortigaunts, provide an entertaining rhythm to the fight and the houndeyes can quickly overwhelm you with numbers. The design of the alien creatures is also excellent overall, which is proven by their longevity, as seen in VR, with minor changes, on the latest title in the franchise. A special shout-out to the ichthyosaur, too, an enemy that managed to terrify me well into my twenties and sometimes still gives me a good scare even now, despite the archaic graphics and animation.

The real highlight where it comes to the enemies, however, is arguably the human soldiers (whom the hardcore fans would call the “Hazardous Environment Combat Unit”, although that title was only established in the game’s first expansion pack). While there’s certainly a lot of trickery involved in making them appear smarter than their AI actually is, there’s no denying that they can put up a decent fight and appear smarter than even enemies in modern games. They’ll force you out of cover with grenades, try to flank you, run for cover and (seemingly) communicate in order to take you down. This goes double more so for the late-game Black Ops assassins, who can give you even more trouble and, in Hard difficulty, even cloak themselves invisible, making them harder to catch.

The world also comes alive through the clever use of enemy factions and situations where both human and alien sides are seen together. Even twenty-plus years later, it never gets old to find the grunts and the Xen invaders in a bitter fight for survival, even more so knowing you can either intervene or just wait it out and deal with the remaining stragglers. It’s a trick that’s been used countless times since, both by its sequels and by many other games, but in Half-Life it has the added quality of reinforcing the notion that Black Mesa has gone to hell and all these events are much bigger than you alone.

Let me take a moment to also praise the spectacular sound effects and ambience. Although some of the audio can sound extremely compressed, it all works wonderfully to build the atmosphere and rhythm of the game, as does its techno-esque soundtrack. A lot of the game’s charm and aura comes from the fantastic work of former Valve sound designer Kelly Bailey; there’s a reason why you can find so many memes of Half-Life sounds on YouTube and why certain clips are so immediately recognizable. Graphics may age, but audio, luckily, not so much.

Eventually, as the Marines find themselves pushed back by the alien infestation, the player makes their way deeper into the facility towards the Lambda Complex, where a final teleporter awaits to send them over to the other side to close the breach between worlds once and for all. Which brings us to Xen.

A nasty piece of work

For about three quarters of the game, Half-Life is a thrilling and creative ride, full of new challenges at every corner, an interesting world and a foreboding sense of the familiar being invaded by the otherworldly. Inevitably, the story leads the player to see what lies beyond, and the first impression is positive… if only for a few seconds.

For its time and the limitations of the engine, the borderworld Xen, at the very least, looks cool at first. Floating asteroids in an auroral void is certainly an aesthetic choice, but visually it grows old incredibly fast as the same elements are repeated ad nausem, unlike the Black Mesa facility, where, for the most part, different sections of the facility had their own particular style—even a casual player can quickly distinguish the relatively mundane offices of Office Complex from the lobby and laboratories of the later chapter Questionable Ethics, for example, but much of the final chapters of the game are virtually indistinguishable save for a change or two of skybox.

Likewise, it’s no surprise to learn that the finale of the game was essentially rushed as the game approached its deadline, because the faults of this part of the game go beyond its repetitive look. Starting off immediately with jumping puzzles—with completely different gravity from the rest of the game, no less, throwing off even the most skilled of players—, Xen (the chapter, albeit much of this applies to this whole section of the game) quickly grows tiresome with unfair and overwhelming fights, as more and more vortigaunts and alien controllers are thrown at the player when ammo is already in short supply, something that only worsens on the harder difficulties.

Eventually, the player stumbles onto the first of the two big bosses of Xen, the Gonarch a.k.a. Big Momma, a massive headcrab whose design isn’t nearly as creative as the rest of the creatures—”giant testicle on a 20-foot-tall armored spider” was literally the briefing—and whose boss fight is very underwhelming and goes on for far too long, with three different phases where you’re doing much of the same.

Things unfortunately don’t improve as the player moves into the last two chapters of the game. If Half-Life stood out by virtue of being more than a corridor shooter and creating an authentic sense of place, then Interloper is the exception to the rule, throwing multitudes of vortigaunts, alien grunts and controllers at you non-stop as you crawl towards the final boss. While there’s some hints of interesting verticality on a select few of the later maps, most of this section is a slog and honestly feels completely out of place in Half-Life—it could easily pass for a bland Doom clone from the mid-’90s and has none of the creativity, atmosphere and enjoyment of the rest of the game. Plus, on Hard difficulty, it’s borderline impossible to get through without save scumming, as ammo, already in short supply, gets increasingly scarce while the enemies you face only grow in number and resilience.

Ultimately, Half-Life culminates with a final boss battle with the Nihilanth, a massive fetus-like creature floating in a dark chamber and seemingly the cause for the rift between worlds remaining open, who’s been taunting you throughout your Xen journey. Much like the Gonarch, the Nihilanth, however imposing, is pretty disappointing, with the portals he shoots to teleport you around being fairly annoying if you can’t evade them in time. At the very least, he’s far more interesting than the headcrab matriarch, with endless debates and analyses prior to and after the release of Half-Life 2 regarding his larger role in the saga.

Still, that’s probably not what’s on your mind as you beat the mastermind of the alien slave forces and finally reach the somewhat abrupt and open-ended ending of Half-Life, where you have a final choice to make before the credits roll to the sound of a truly fantastic song. Much has been said about the end of Half-Life (and eventually Half-Life 2), but, without spoiling anything for new players, I will argue that it fits the game—just as you open in media res for a seemingly normal work day, it ends on a similar note, albeit a much more uncertain and eerie one, clearly leaving the door open for the inevitable sequel (which we’ll eventually get to at some other time).

Half-Life or Black Mesa: which one should you play

Before we move on to the conclusions, a brief aside to discuss the Gargantua in the room: whether you should play the first Half-Life at all or jump straight to its fan-made Source remake, Black Mesa, something that even a developer of the original Half-Life is prone to do.

While we’ll inevitably do a review for Black Mesa as well at a later date and perhaps even an article on this topic alone, the short answer is: you should definitely play Half-Life, regardless of the remake. While Black Mesa certainly looks a million times better, in the end, it’s a very different game from the original, and not necessarily a better one, Xen notwithstanding. Look past the graphics (and maybe activate the High-Definition Models on the options menu if that’s your cup of tea) and you’ll find a game that holds up to the test of time in most regards. Play the original first, then give the remake a go later, you’ll appreciate both more.

Whatever you do, just don’t play Half-Life: Source. Trust us.

Final thoughts

Half-Life feels very much like two games in one, although, regrettably, that’s not a good thing. For the majority of its runtime, you have a nearly flawless romp that ebbs and flows from survival horror into full-on action, one that has aged wonderfully if you can look past the archaic graphical fidelity. However, as it reaches what should’ve been a spectacular climax, it instead becomes a grind you’re almost happy to see end.

However, if the past twenty-five-ish years have shown anything, it’s that even the rush job that was Xen didn’t color people’s impressions of Half-Life. There’s a lot more good than bad here and a couple of, at worst, mediocre hours don’t ruin the overall experience. The original Half-Life is still a nearly flawless experience and one that every self-respecting gamer should play through at least once—though there’s no shortage of extra content, from the official expansions to literally hundreds of mods and map packs, to expand your trip to the Black Mesa Research Facility.

If you haven’t played it in a while, go back and reexperience it all over again. If it’s your first time, then grab your crowbar and face the unforeseen consequences of your actions. Trust me when I say that life will be different.

Half-Life is available for purchase on Steam.

I think you should play Half-Life first and then Black Mesa. Overall great game, must play for everyone!

What a succinctly well reviewed article, this. I’ll add some things, though: one, no need to install the HD Pack, that actually muddies the already nice enough graphical quality of, say, the guns (honestly, I’d rather have the MP5 than the Colt 727; also, don’t trust Gearbox and its head, who is the living embodiment of grease with the initials R.P.). Two, I recommend newcomers to try out the classic game first BEFORE Black Mesa, not only to be not spoiled by the remake’s beauty and changes, but also to have a well established foundation and respect for the classic version that will easily stay in your memory and familiarity (as my personal experience to the likes of Doom and TIE Fighter have proven to ruin my experiences on Wolfenstein 3D and X-Wing respectively back in the day). Finally, three, yes, ignore HL: Source… its flawed existence is one of the very big reasons why Black Mesa exists.